The acceptance, however, did not come easy, Ngainten told thejakartapost.com.

Hearing the truth come out of Gunawan's mouth was shocking even though she had figured out her son's sexual orientation herself.

"How could my strong and handsome son become like this? What mistakes

did I make? But nonetheless, he is my son. I won't hit him or shout at

him because being homosexual was not his choice," Ngainten says during a

telephone conversation.

Embracing her fifth child's sexuality was the only right thing

Ngainten felt there was to do, fearing that if she pushed him away she

would risk losing her son.

"Gunawan is my most obedient son. I accept who he is just like my

other children. I gave birth to him," the woman says, adding that she

also feels glad her husband has shown the same acceptance as she has.

Ngainten says she also ordered all her children to accept their brother without any discrimination.

Relieved and happy was how Gunawan felt after coming out to Ngainten,

the woman who had given birth to him and his seven siblings.

However, happiness had not always been Gunawan's best friend.

He had kept his sexual identity a secret until coming out to other

gay people when he was 26 years old, around the same time he met his

future husband.

Coming from a Muslim family in Jombang, Gunawan had been hesitant to open up about his feelings.

Asked about any discrimination he had received, Gunawan rolled his

eyes. "Oh my God," he said, followed with a loud laugh that felt like

just a disguise for a somewhat painful experience he had gone through.

He recalls being attracted to his seatmate in junior high school and

that started all of the questions he had for himself. A 13-year-old

Gunawan could not comprehend why he would have a crush on his male

friend.

He was bullied by his friends all through junior high school and high

school for having effeminate traits and spending more time with girls.

From a young age, Gunawan says he felt more comfortable befriending

girls than boys, adding that he even considered boys as something alien

to him.

He called the experience “painful”.

The bullying caused trauma, forcing him to let out all of his confusion by crying alone as he had no one to talk to.

"I was afraid if I told my mother she would reject me and if I told

my teachers they would blame me. I tried to handle it myself," said the

businessman who also volunteers at an NGO called Kemitraan where he

helps to advocate on human rights issues.

The bullying stopped, luckily, during his university years although he had still not opened up about his sexuality.

Gunawan remembers that during high school and university he repressed

his sexual attraction to men and hid his sexuality altogether. His

close friends at university taught him to act like a masculine man and

how to walk in a manly manner.

He thought he was cured; a defunct homosexual.

That was until he fell in love again, with another man when he was

25. Confusion re-appeared and flashbacks of what had happened to his

younger self flooded his mind.

To his hometown then, Gunawan returned. To seek enlightenment, he

went to local clerics as he had no-one to talk to. No institution or

professionals that he knew of could help him.

"It forced me to go to my village in Jombang to learn more about my

religion; to know what my religion's perspective on homosexuality was,"

Gunawan says.

Homosexuality is wrong. That was the only answer he received from the clerics.

Nevertheless, hearing that answer first hand did not erase the affections he had for the man.

Gunawan then turned himself to books. He read books on psychology and

human behavior to find the answer to the question that had lingered in

his mind since he was a teenager.

Then, to feed his curiosity when he was 26 years old, he started to join internet chat-rooms for the gay community.

This provided a new perspective for Gunawan. He found out that he was

not alone. There were people like him who also felt attracted to people

of the same sex. It was the first time he felt truly comfortable with

himself, leading him to come out to the friends he met through the

chat-rooms.

Through online chatting as well, Gunawan met de Waal in 1998.

What started as casual conversations quickly turned into a battle of

wits. Gunawan remembers vividly how he did not immediately get along

with the Dutchman.

He explains how at first they felt they were too different to each

other, not only because of their cultural backgrounds but also their

tastes and points of view. Deciding they were better off as friends, it

wasn't until over a year later that they took their friendship to the

next level and became lovers.

The pair spent 16 years in a committed relationship before deciding it was time for them to make things official as a couple.

With a bashful laugh, Gunawan talks about his wedding to de Waal in the land of clogs and cheese on August 1, 2014.

Smiles and happy tears adorned the intimate moment the pair shared with their loved ones.

Gunawan later uploaded one of the happiest moments of his life to his

Youtube channel. The slideshow of photos shows the longtime couple in

similar blue shirts and trousers with subtle gold patterns, completed

with batik fabrics worn round their hips: the traditional-meets-modern

Indonesian groom attire.

He says it was never his intention to provoke the Muslim-majority Indonesian public to follow his ways.

"We have no other purpose other than to share our happiness with our family and friends," he said.

Gunawan admits at first he set the video to private viewing only for

his friends and relatives across the two continents. However, an unknown

person downloaded the video and shared it anonymously at de Waal's

office in Jakarta, leading to the couple receiving threats.

Nevertheless, the pair found meaning in the incident. After hiring a

lawyer to help them consider taking legal action, Gunawan decided, after

some consideration, to instead make the video public.

The video, titled "Hans & Gunn Wedding", uploaded to

his Youtube channel “Gunawan Wibosono” on Oct. 24, 2014, contains the couple’s wedding photos and has so far garnered more than 12,000 views.

"I want to show people that even as LGBT people, we can find love, we

can find long-term relationships and we can get married," he said, with

heartfelt gratitude evident in his voice.

"But probably, I'm one of the minority who was fortunate enough to be able to marry abroad."

Public uproar on LGBT rights

Despite Gunawan's confidence in outing himself and sharing his

personal life, discrimination against LGBT people in Indonesia has been

growing louder recently.

Government officials and religious leaders have publicly stated they

are against sexual orientations that they say deviate from the morals

and values of the national identity and religious norms.

Although homosexuality is not illegal in Indonesia, it remains a sensitive issue.

Supporters of rights for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual,

Transgender, Intersex and Questioning (LGBTIQ) people protest at the

Hotel Indonesia traffic circle on May 17, 2015. The protest, which was

held to celebrate International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and

Transphobia, called for an end to violence and discrimination toward the

LGBTIQ community. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

Supporters of rights for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual,

Transgender, Intersex and Questioning (LGBTIQ) people protest at the

Hotel Indonesia traffic circle on May 17, 2015. The protest, which was

held to celebrate International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and

Transphobia, called for an end to violence and discrimination toward the

LGBTIQ community. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

Heated debate about the LGBT community exploded into the limelight

earlier this year following a remark from Research, Technology and

Higher Education Minister Muhammad Nasir saying LGBT people should be

banned from university campuses.

He was reacting to the presence of a community-based organization at

the state-run University of Indonesia called Support Group and Research

Center for Sexual Studies, known as SGRC UI.

The minister suggested the LGBT community's presence was "corrupting

the nation's morals", which inspired a slew of statements in response.

Other ministers joined in, making hostile statements against the

minority group, calling them a threat to the state's religious life and

even suggesting LGBT people be provided therapy to cure them.

Indonesia's Islamic administrative body, the Indonesian Council of

Ulema (MUI), condemned LGBT people, issuing a fatwa that declared their

activities haram, (against Islamic law) back in 2014. Recently the body

went as far as calling for legislation to ban LGBT activities.

MUI chairman Ma'ruf Amin said the council supported criminal

punishment of anyone that engaged in LGBT sexual activities, or

encouraged, promoted or financed activities connected with the LGBT

community.

Read also: MUI wants law to ban LGBT activities

Although MUI's fatwa is not legally binding, it is considered a

strong recommendation by conservative Muslim groups in Indonesia that

often do what a fatwa states.

A group opposing the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and

Transgender (LGBT) community prepares to confront a pro-LGBT group

planning on staging a counter protest at Tugu Monument in Yogyakarta on

Feb. 23.

A group opposing the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and

Transgender (LGBT) community prepares to confront a pro-LGBT group

planning on staging a counter protest at Tugu Monument in Yogyakarta on

Feb. 23.

(Antara/Andreas Fitri Atmoko)

Many hard-liners have shut down discussions on LGBT issues, including

forcing authorities to close the Al Fatah Islamic School for

transgender people, established in 2008 in Yogyakarta, in March.

Read also: Authorities shut down Yogyakarta transgender Islamic school

Popular South Korean-based mobile chat application Line also conceded

to government warnings and removed stickers featuring same-sex couples,

also issuing an official apology.

Moreover, the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) has enacted a

rule that discriminates against LGBT people. The KPI said it discouraged

broadcasters and television and radio stations from running programs

that promoted the activities of the LGBT community and banned effeminate

men from being portrayed on national television to, they claimed,

protect children and teenagers from exposure to that “lifestyle”.

In the latest attempt to suppress the LGBT community, the Islamic

United Development Party (PPP) lawmaker Hasrul Azwar announced a plan in

April to propose a bill in the House of Representatives to regulate

what he called “LGBT propaganda”.

The PPP’s bill was first proposed by the Indonesian Muslim

Brotherhood (Parmusi), one of the organizations that helped establish

the Islamist party. The party deemed LGBT groups a danger to social

relationships and stated that related practices were prohibited by

religion.

The leading Indonesian psychiatric body has also classified

homosexuality, bisexuality and transgenderism as mental disorders, which

it claims can be cured through proper treatment.

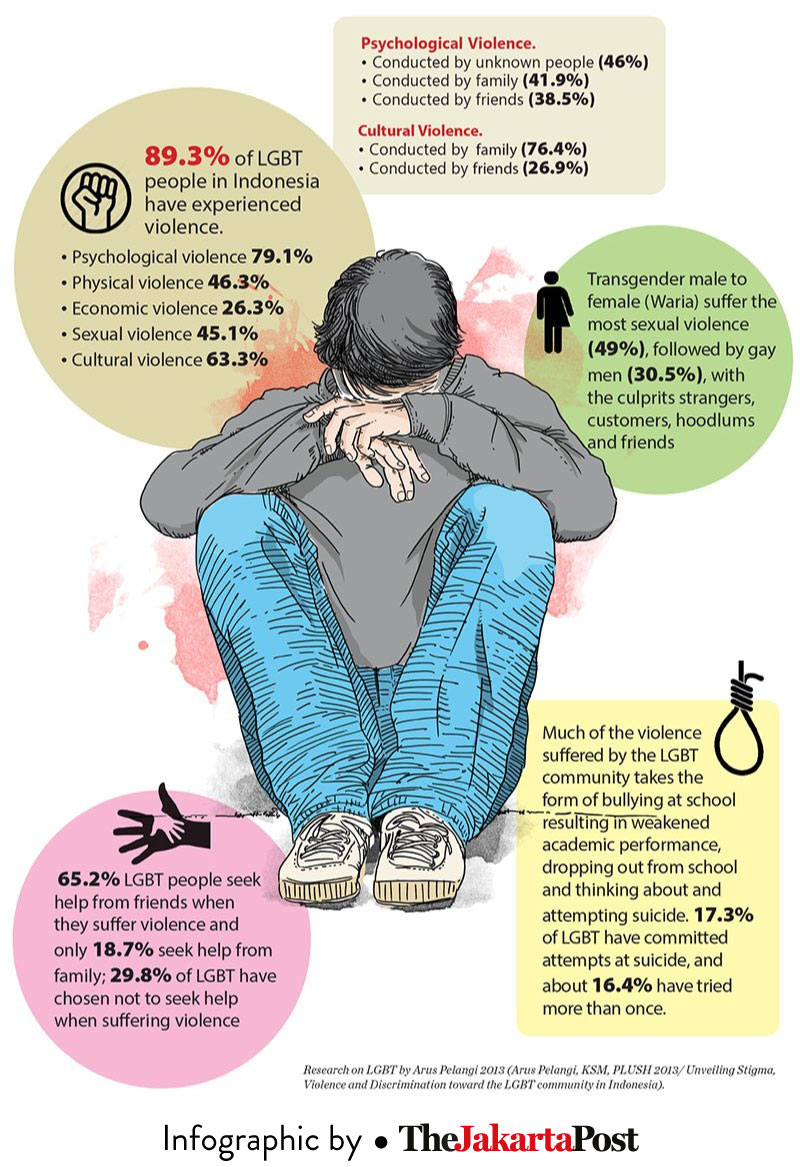

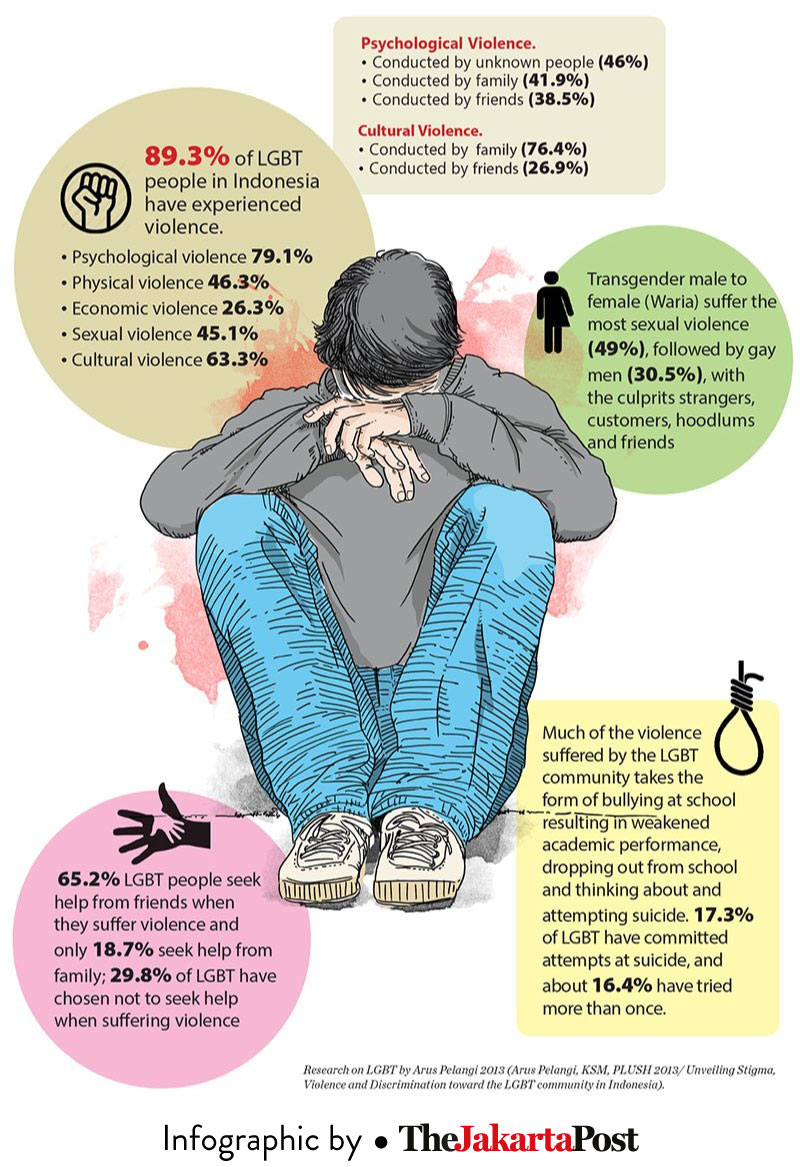

Arus Pelangi, KSM and PLUSH in 2013

produced a research study titled 'Unveiling Stigma, Violence and

Discrimination toward the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT)

Community in Indonesia', based on information from 335 LGBT people in

Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Makassar. (JP info-graphic/Budhi Button)

Arus Pelangi, KSM and PLUSH in 2013

produced a research study titled 'Unveiling Stigma, Violence and

Discrimination toward the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT)

Community in Indonesia', based on information from 335 LGBT people in

Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Makassar. (JP info-graphic/Budhi Button)

Suzy Yusna Dewi, member of Indonesian Psychiatrists Association

(PDSKJI), said the aforementioned sexual identities were often triggered

by external factors such as a person's social environment, and

therefore, they could be healed through psychiatric treatment.

Read also: Indonesian psychiatrists label LGBT as mental disorders

The PDSKJI defines homosexuals and bisexuals as “people with

psychiatric problems” while transgender people have “mental disorders”.

The classifications are in stark contrast to those of the World Health

Organization (WHO), which removed homosexuality from its list of

psychiatric disorders on May 17, 1990.

LGBT support group

The controversy surrounding LGBT issues in Indonesia thrust UI’s SGRC

into the media spotlight at the beginning of the year following the

remarks Minister Nasir’s made when he was first informed about the

organization's existence.

Nasir's banning of LGBT groups from university campuses, because such

institutions were the “safeguard of the country’s moral values”, soon

put SGRC in the headlines.

Members of SGRC, consisting of students, alumni and lecturers of the

most prominent state university in the country, particularly felt the

heat at the time.

SGRC head of studies 20-year-old Fathul Purnomo says the group

focuses on sexuality studies such as feminism and gender and minority

issues. The group also provides counselling to support LBGTIQ students.

Every two weeks the group holds an academic discussion event called

"Arisan". Also, those who want to get counseling can register and the

committee will get them in touch with a counselor who can help them, he

added.

"We'll refer them to a counselor to help to relieve their pain,

relieve the pressure they feel from society, relieve pressure such as

that caused by the minister of higher education, about their sexual

preference and being excluded from society," the philosophy-major

student said.

Fathul joined the group as one of its first members in its early days after it had just been launched on May 17, 2014.

The members of SGRC – both committee and regular participants – are not limited to LGBT people, Fathul says.

In fact, he says, there is a diversity of backgrounds, including

people who are liberal, conservative and also religiously devout people.

Fathul expresses disappointment in the media's misrepresentation of

the group, with local headlines recently labeling SGRC a dating platform

for LGBT people.

The stories raised many eyebrows and attracted criticism, especially from those who oppose the LGBT community.

Some members of the SGRC still feel the trauma of that experience today.

Some were ex-communicated from their families due to embarrassment

about their affiliation with the group, while others felt such heavy

pressure that they had suicidal thoughts.

The media madness brought on some trouble for the group, including

the university cutting them off its list of student organizations.

Previously named SGRC-UI, the group has now dropped the "UI" from their official title.